Summary

The oil and gas industries face several long-term challenges: On the one hand, demand and pricing are likely to be constrained by the impact of alternative/renewable energy supplies and by environmental considerations. On the other, the increased technological challenges associated with more complex processes to discover and extract oil will increase cost and risk.

The future success of the sector will be closely linked to its ability to attract investment. This will more than ever depend on robust project selection, efficient projectmanagement, andsophisticated portfolio optimisation. The success of individual companies will partly depend on their ability to generate a deep understanding of project economics, and to use this understanding to create more robust decision-making processes, and to improve outcomes in negotiations with private sector partners and governments.

In this article, we highlight the key benefits and challenges in using risk and uncertainty techniques to support decisions relating to project evaluation, selection and portfolio optimisation. We note that over recent decades, the industry has made great strides in its approach to assessing and managing safety and operational risks: Regulations and guidelines have generally continued to be improved andadapted, andorganisationalprocesseshavebeendevelopedtoidentify, mitigateandmanageawiderangeofoperationalrisks, even as sometimesthishasbeeninresponsetodisasters. However, wearguethatanalogousapproachesfordecision-supportaregenerallynot yet adequately embedded within organisational processes and cultures, and that they are not implemented in a systematic manner. We emphasise the benefits in doing so, whilst also highlighting somekey challenges. Wearguethat top-down leadership is essential in order to succeed and to embed the appropriate “risk culture” within an organisation.

Whilst noting that the key challenges are of an organisational and cultural nature, we also briefly mention some technical tools that are typically required, such as simulation techniques.

Weconclude by noting that the issues highlighted here are similar in Vietnam to those in many other geographies around the world, even as the extent of implementation varies. In order to maintain a competitive advantage for Vietnam, it is important to enhance industry culture, capabilities and decision-making processes without undue delay.

Key words: Risk management, benefit, challenge.

1. Introduction

Risks and uncertainties are present in almost all areas of the oil and gas sector, from upstream to downstream, and from operational areas to those relating to strategy and financing.

For example, there are many risks associated with operations: These include hazards within the extraction process, fire risk, crane accidents, leaks, spillages, diving or other occupational accidents, general health and safety, as well as transportation, collisions and so on. Similarly, there are many risks and uncertainties that affect the economic profitability of major projects. These include the success or failure at the exploration or appraisal stage, uncertainty about the sub-surface volume and recovery levels, the capital expenditure required, the production profile, and the level of future operating costs. The overall success of a project, portfolio or business is also affected by factors such as price level, the potential for substitute products in end-user activities, and issues relating to environment/ climate change, and government and international policy decisions. All of these affect the potential to create value within the sector and, crucially, to be able to generate a return-on-capital that is sufficiently attractive for potential investors.

In such a context, it is self-evident that one key factor that will determine the success of the sector (and create a differentiation between companies within it), is the ability to effectively assess, evaluate and quantify risks and uncertainties when evaluating investment projects, and to use this to inform decision-making and negotiations with private sector partners and governments.

In this article, we briefly note the progress that has been made by the safety and operational side of the industry over the last 40 - 50 years, in terms of introducing risk assessment and management processes. We note in comparison the relative lack of systematic risk assessment for the financial evaluation of projects. We discuss the importance of such approaches, the consequences when sufficiently robust assessments are not conducted, and the main challenges to achieving a successful transformation to a “risk culture”. We note that a critical success factor will be the need for such changes to be driven top-down by industry and company leaders.

2. Requirements for the successful management of risk and uncertainty

This section briefly summarises some core requirements and characteristics of organisations that are most successful in their approach to risk and uncertainty assessment, focussing on the topics of awareness, processes and culture.

Awareness

The first component of being able to manage anything successfully is awareness of the issue. Whilst we as humans are often naturally aware of risks in many situations, we also seem to be programmed to deliberately ignore information about risks, especially where we feel that we do not understand them, cannot manage them, or if knowledge about them could bring unpleasant news or require us to change our existing beliefs (see later for a more detailed discussion of this). This concept of “information avoidance” or “deliberate ignorance” is a key challenge.

Processes

The effective assessment and management of risks requires formalised multi-functional processes. These include definitions of the types of analysis required, the criteria to determine the most appropriate approach and the way that the information generated should be used to support decisions. For example, a full quantified risk assessment may be required for all projects above a certain size, or where there is some key aspect to the project that is new, whereas a simplified form of analysis may be sufficient for smaller projects. These have knock- on implications for issues such as skills development and general organisational processes.

Culture

The most challenging component to successfully assess and manage risks and uncertainties relates to organisational culture. This has many facets, as discussed later. A “risk culture” is one in which there is a general, widespread and shared belief in the absolute requirement to formally assess risks and uncertainties, and a converse belief that a lack of such activity would likely lead to sub- optimal decisions in general.

It is worth noting that not only are all three components simultaneously necessary, but also that there is some interaction and overlap between them. For example (where one accepts that not all elements of a project are fully controllable), the issue of appropriately managing incentives is a complex one, and which involves all three components.

3. Progress made in the operational side of the industry

Over the last 40 - 50 years, the operational side of the industry has developed many processes to identify and manage risks, and these are now widespread and used reasonably systematically in most key areas that affect operational and safety matters.

Such developments were often driven by the need to respond to major events. For example, the Cullen report into the 1988 Piper Alpha disaster in the UK [1] stated that “Quantitative Risk Assessment… would be a valuable source of information to aid decisions about safety provisions offshore”. Further, several countries have been particularly proactive in continuing to develop, improve and document general procedures for risk assessment [2]. To a large extent, these have been transmitted and adopted around the world, not least due to the global nature of the industry and its many partnerships and joint operations.

However, the path taken has not always been straight nor without its difficulties, and the process is not complete. For example, the report(s) issued by the Deepwater Horizon Study Group stated that “This disaster was preventable had existing progressive guidelines and practices been followed. This catastrophic failure appears to have resulted from multiple violations of the laws of public resource development, and its proper regulatory oversight”. Further it is stated that “there were perceived to be no downsides associated with the uncertain thing…” and that “BP’s corporate culture remained one that was embedded in risk- taking and cost-cutting”.

Thus, although the path is not complete, and there are new challenges as extraction becomes more complex, it is fair to say that there is a widespread and strong awareness of risk- related issues, and a well-developed set of processes that are documented and can be followed in order to assess risks in these operational and safety contexts.

4. The consequences of insufficient assessment of risk and uncertainty in project evaluation and business strategy

In this section, we focus on the potential consequences of a lack of uncertainty assessment in the evaluation of projects and business cases. These are of course measured in financial terms, rather than health and safety or operational outcomes. It is worth noting that whilst the rest of this section discusses specific consequences of insufficient consideration of uncertainties (and so is arguably framed in “negative” terms), the discussion could (and should in many cases) equally be represented in a positive frame. The benefits achievable are essentially the opposite of the disadvantages of not conducting risk and uncertainty assessment in a systematic manner, and so, for the sake of conciseness are not covered explicitly here in detail.

Before discussing the consequences in detail, it is helpful to discuss a simple example which illustrates some of the quantitative outputs of uncertainty assessment and highlights some core principles which are partly developed further in later sections.

A simple illustrative example of quantification

Suppose that one wishes to assess how much time a friend will spend travelling to work over the next 10 working days. One may start by asking the friend a simple question: “How long does your typical journey last?”. This is a natural and intuitive approach, and it would be fairly common for an answer to be given as a single number (such as 45 minutes) without any explicit consideration of the possible various scenarios or uncertainty ranges for the journey time.

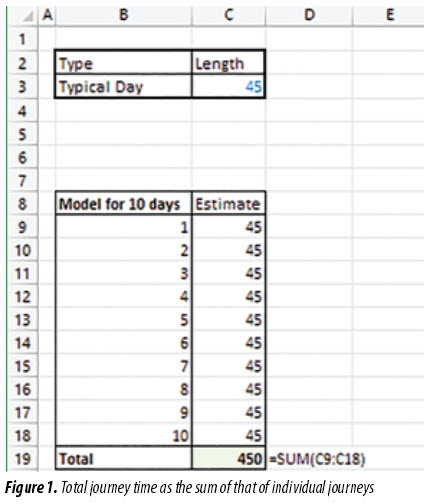

To estimate the total time requirements for 10 journeys, one would then typically simply multiply this estimate by 10, or more generally add together the figure for each day’s journey, perhaps in an Excel model in which each day is represented by an assumption for that day’s journey time. Figure 1 shows such a model, in which the best estimate (45 minutes) is used for each day’s journey time, with the calculated output showing a total time of 450 minutes.

It is conceivable that, conscious of the potential uncertainty, one may use heuristic judgment to estimate a range around this total figure, such as the total journey time being “450 minutes plus or minus 10% (45 minutes)”.

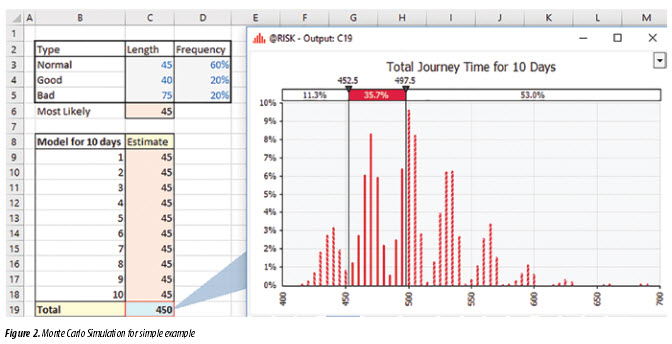

When thought of in probabilistic terms, the “best estimate” would usually correspond to the most likely of a set of possible values that could occur. For example, from experience it may be known that the most likely case (45 minutes) would occur for 60% of journeys, whereas in 20% of cases the journey may be slightly quicker (40 minutes), and in another 20% of cases, it could be longer (75 minutes), perhaps due to bad weather, traffic accidents or other “event risks”, etc. Generally, the time gained through good journeys may not be totally compensated by that lost through bad ones (i.e. the possible times are not distributed symmetrically around the most likely value). Note that even where the friend has given consideration to uncertainty before providing an answer to the original question, the requirement to provide a single number will typically mean that the answer provided represents the “best estimate” of the journey time.

In fact, a formal uncertainty analysis (using statistical methods or simulation techniques) would show that the average total journey time is

500 minutes, i.e. that 450 minutes is not the central point of the possible range. Further, the“base case” estimate of 450 minutes is exceeded with a frequency of approximately 90%. Indeed, the worst case estimated heuristically (i.e. 495 minutes or 450 minutes plus 10%) is still less than the average or central value. These values are demonstrated in Figure 2, which have been calculated using Monte Carlo simulation with the Excel add-in @RISK®.

Note that the same principles would likely apply in many other situations or projects, such as estimating the costs or capital expenditure for a project. Thus, these projects may have little chance of being delivered within the base budgets that have been defined using traditional methods.

This simple example highlights several important points:

• That much analysis of business cases is subject to the “trap of the most likely”: This is the belief (usually implicit) that a forecasted base case reflects a “central” case whenever the input assumptions are in the “central” region of the possible range. In fact, even where a model’s input assumptions are chosen to be in the “central” region of their individual possible ranges, the output case shown may be at a relatively extreme end of its true range.

• More generally, there is no correspondence (in terms of definitions) between a model’s inputs and its calculated values; it is difficult (unless risk techniques are used) to determine how optimistic or pessimistic a calculated value is, based on the potential optimism or pessimism in individual input assumptions. Thus, the“base case” of many models is in fact very imprecisely defined.

• That, when several uncertainties are present, it is difficult to estimate (without using risk assessment) their overall effect on the possible range: Why it may be intuitive (after some reflection) that the base case output of the above analysis would not be in the central range, the location of the central point as well as the extent of the possible deviation around cannot be estimated reliably by informal judgment or even by traditional sensitivity analysis.

• If base case assumptions were biased for other reasons (motivational, political, or cognitive reasons) the problem of estimating true range is further compounded. For example, the base case may have assumed a single day’s journey time of 42 minutes (rather than the true most likely figure of 45 minutes). In fact, what may appear to be a small bias in each individual input assumption will lead to much larger biases in aggregate: As can been seen in Figure 2, a total journey time of 420 minutes (i.e. the base case in this example) would arise only very infrequently. For a more complete discussion of such phenomena, [3].

It is interesting to note that, in principle, the activities of project evaluation, business planning, and portfolio selection naturally require the use of quantitative techniques. The default approaches (e.g. for business case analysis using Excel) typically use fixed values for input assumptions augmented with sensitivity or scenario analysis. Given that uncertainties are ubiquitous in any project, one may ask why risk and uncertainty assessment is not automatically used as the default approach instead (i.e. to use models or analysis which simply reflects the reality of the situation).

Taking on incorrect projects or miscalculating their likelihood of success

Without an adequate risk assessment, even where the “base case”financial evaluation seems positive, the project may in fact have a low chance of success, or a high chance that financial expectations are not met in some way (cost or CapEx overruns, reduced revenues etc.). This has been illustrated with the simple example above. As noted, traditional analysis uses an ill-defined base case, and one which would mislead as to the true likelihood of achieving a specific project objective. In extreme situations, one may therefore accept a project which in fact has a low chance of success (or reject one with a high chance of success). In less extreme situations, the true likelihood of a project achieving its expected objectives may be much lower than originally believed if risk assessment approaches are not used.

More generally, the uncertainties that are present should be reflected in any analysis order to have information that is reliable to support decisions. Such analysis would use a structured process to include all relevantfactors, itwouldincludeeventrisks, non-linearities (e.g. the potential to react flexible or real options), as well as correlations or more complex forms of dependency ([3] for more detail about modelling approaches).

The use of risk and uncertainty assessment can therefore help to ensure that one has a realistic assessment of the likelihood of achieving the objectives.

Authorising too few projects, sacrificing growth and profitability

Without a robust process to assess risks and uncertainties, one may inadvertently make overly pessimistic assumptions for capital expenditure or cost items. For example, within a project, it is not likely that all risks will materialise (and that within a portfolio, not all projects are likely to go wrong). Whilst one may be aiming to plan or budget “conservatively”, in fact, the compound effect of being conservative in several areas typically results in excess conservatism, and one which is almost impossible to correctly assess using judgment. In other words, without an adequate assessment, one may plan for too much contingency, and hence reserve capital unnecessarily, so that other possible projects cannot be authorised or undertaken, thus reducing growth or profitability.

Growth can also be sacrificed if too few projects are authorised based on excessively optimistic assumptions about their success. For example, if a company’s growth objectives can be achieved through having three successful exploration projects, then an (overly) optimistic approach could be to undertake only three projects; in reality, only one or two would succeed, so that growth objectives are not achieved after all.

The use of risk and uncertainty assessment can therefore help to ensure an appropriate balance between optimism and pessimism in budgeting, planning and long-term business strategy, especially where there are significant growth objectives that are desired to be met.

Authorising too many projects, increasing growth but reducing profitability

A poor risk assessment could lead to projects being authorised even when they have little chance of success (as discussed above). More subtly, as a “mirror-image” of the above discussion, an overly optimistic approach to capital expenditure or cost estimates could result in too many projects being authorised (in terms of genuinely available capital), so that planned contingency budgets are insufficient for the risks that materialise. As a result, even projects which are inherently profitable may run out of budget and become delayed, which will reduce profitability or may lead to forced sales or the need to raise additional financing at short notice.

The use of risk and uncertainty assessment can once again help to ensure an appropriate balance between optimism and pessimism in planning and long-term business strategy.

Designing sub-optimal projects

A risk assessment process that is not conducted adequately will typically result in projects having been designed in sub-optimal ways. This is because the process of risk assessment and mitigation/response should generally result in a change to the initial design of a project, so that the revised project is designed in the optimal way given its risk structure and the possible mitigation measures. One may develop several project options or design variations, from which one can choose the best. Similar comments apply to portfolio construction, where uncertainty assessment can assist to design better portfolios (e.g. creating portfolios so that cash generation in some projects best matches cash requirements in others).

Insufficient transparency and hidden biases

Biases can take many forms: cognitive, motivational/ political or structural. Cognitive biases are those that are inherent to the human psyche and are believed to have arisen for evolutionary reasons. Motivational or political biases are those where someone (or a group) has an incentive to deliberately bias a process, a set of results, or the assumptions used. Structural biases are those created by the choice of a methodology or tool set. As noted in the simple example earlier, the traditional static approach to analysis using fixed numerical assumptions will often create a structural bias, and “base cases” are typically not clearly defined.

Whilst there may sometimes be valid (e.g. commercial) reasons for working with biased cases (such as when presenting a negotiating stance to a commercial partner), surely the most robust decisions can be made only if one knows the extent of these biases (even if only for internal use).

The uncertainty assessment process (particularly when quantitative) can help to discuss and expose such biases. First, the process to simply ask: “Why could the outcome be different to the one we have assumed?” can highlight that the assumption is not within a central region of the possible range. Second, a robust quantitative model will totally separate the value used for the base case (fixed) assumption of a variable from the possibility uncertainty range (probability distribution) for the values of that variable. The treatment of these as separate issues (and as separate modelling assumptions) will help to expose the biases (especially those that are structural, political or motivational). Thus, a lack of adequate consideration of uncertainty hinders the process to expose and (potentially) correct for biases.

Ineffective group working processes

In some cases, a lack of consideration of the uncertainty can hinder working processes. Although uncertainty analysis may appear to be more complex than traditional static analysis (and it generally is so), the fact that traditional approaches do not reflect the reality of a situation can sometimes hinder working activities.

As a simple example, given a set of exploration projects (each of which could succeed or fail individually and independently), a working group that is asked to budget for the required subsequent capital expenditure (i.e. that required to move beyond the exploration phase for successful projects) may have difficulty to decide on which scenario to plan for: When using traditional static methods, the group will need to first decide on a specific case to plan for, even though this is not realistic (e.g. perhaps by assuming that 3 out of 5 projects will succeed). Time will be spent discussing and deciding which fixed scenario to plan for, and biases in views on such issues can also hinder this process. On the other hand, a risk approach would allow for all valid scenarios to occur, and shift the discussion to the more realistic, practical and value-added topic of how much contingency budget is necessary, given the uncertainty in the required capital expenditure.

Uncertainty analysis can also reconcile conflicting views in some cases: An uncertainty distribution (for the value of a model’s input assumption) may be able to capture all the valid views and reflect them in the analyses, without having to artificially choose one or the other (which can also be time-consuming, whilst probably not creating value). For example, two experts may each have a different view as to the capital expenditure requirements for a project, and each view may be valid, since it could implicitly represent either general uncertainty or specific scenarios. Once again, a more effective group process can be one which allows both views to be represented rather than having to choose one over the other, or to establish a compromise view that is possibly not even realistic or may be biased.

Thus, in some cases, the use of uncertainty assessment process can help to improve working processes, simply by allowing such processes to focus on discussing the reality of the situation.

Inappropriate decisions and poor corporate governance

The reflection of risk tolerances in decision processes is core to effective corporate governance: The management of a company has the challenge to balance the potential creation of value (through activities which are inherently uncertain) with the need to avoid excessive risk-taking (that could damage the company’s prospects or contravene key principles of corporate governance), and to do so in a way which aligns with the expectations of shareholders or other key stakeholders. Without a formalised risk assessment, one cannot truly achieve this objective in a robust and systematic way. Thus, the lack of quantitative risk assessment for any of a company’s major activities may significantly restrict a management team’s ability to correctly make trade-offs in this respect. Conversely, the use of risk and uncertainty assessment process can help to improve corporate governance in a wide sense.

5. Challenges in creating risk cultures

Earlier, we mentioned the pre-requisites for successful implementation of risk and uncertainty assessment processes i.e. under the topics of Awareness, Processes, and Culture. We have noted that the health, safety and operational side of the business is generally well advanced on the criteria of Awareness and Processes and has made significant (yet imperfect) strides in the area of Culture.

In this paper, we advance the hypothesis that in non- operational sides of the business, the three components are insufficiently developed. Although all three need to be addressed simultaneously, the key challenge will be the development of “risk cultures”. Indeed, a lack of sufficient cultural change will ultimately lead to failure of implementation of the other components. The cultural aspect is therefore key but is the one for which there are the most challenges. The following discusses some key aspects of these.

Human instinct in the face of uncertainty or complexity

Generally, humans seems to be programmed to ignore (or not react to) uncertainties in many types of situations. An important case is informally known as “ignorance is bliss”. The more formal concept of“deliberate ignorance” or “information avoidance” has been explored by academic psychologists [4]. Such behaviour results from an underlying need for “psychological security” (in addition to physical security). For example, the willingness of people to want to know their true risk of developing a disease is very different according to whether that person had been briefed or not as to the actions that one could take to reduce the impact of the disease in the case of a positive diagnosis. The academics tested this in the context of diseases which have significant genetic risk factors (e.g. breast cancer in women, diabetes, cardiovascular risks), so that the risk for any individual could be determined using the genetic profile of that person. For a group which had not been briefed about disease-management measures, the perceived“lack of controllability”leads to a“preference for ignorance”(in which participants often did not want to be tested). Conversely, within groups that have been pre- briefed about possible disease management measures (i.e. where participants then perceive controllability to be higher), there is a desire for the testing to be conducted. The academics note that in general, for reasons associated with “psychological security”, humans tend to ignore risks or uncertainties if we feel that we do not understand them, or cannot manage them, or if knowledge about them could bring unpleasant news, or may require us to change our existing beliefs. On the other hand, we are more likely to consider risks if we feel that we know how to control them, or if the uncertain outcomes could potentially be good for us.

A related instinct when faced with any form of apparent complexity is to “wait and see”, to do nothing, or to search for overly simplistic solutions.

Lack of observability and feedback

In the operational side of the oil and gas business, risk assessment processes are largely concerned with health and safety issues (in the broadest sense of the term). In such contexts, an insufficient assessment of risks can lead to the occurrence of accidents or other events that may have been preventable, whose causes are identifiable, and for which responsibility can often be assigned.

On the other hand, for an oil and gas project that may develop over 20 - 30 years (or longer), its ultimate overall financial success may only become clear in the distant future. At such a time, the original business case on which the project was built is likely to be long-forgotten, or reasons can be found in retrospect as to why the original assumptions used did not materialise. Further, whereas (for example) for health and safety-related accidents, the consequences are often directly tangible and visible, such immediacy of feedback is not availability for the economic parameters of a project which develops over a multi-year time frame.

Indeed, it can be difficult to“prove” that the enhanced processes associated with risk assessment actually “work”, since the overall effect of using enhanced processes is often diffuse (and in the future) and cannot be conducted within a “controlled environment”. For example, due to uncertainty, it is very difficult todistinguishagooddecision from a good outcome (a good outcome can happen even if the decision was poor and vice versa). Further, (by analogy) the fact that it is ill people that need to take medicine does not mean that the medicine is ineffective or not necessary; indeed, risk assessment is more necessary in a world of tight budgets, robust competition and uncertain environments. Yet, the projects that are in most need of robust risk and uncertainty assessment are generally precisely those which are the most challenging, and which may inherently have the highest chance of achieving poorer outcomes.

In summary, generally, the lack of direct feedback between decisions and outcomes increases the challenge relating to the introduction of risk assessment processes.

Responsibility and incentives

Concerning the issue of incentives, it is often the case that the personal consequences for ignoring risks is often none or extremely limited. A specific comment about this was noted earlier where the Deepwater Horizon Study Group stated that “there were perceived to be no downsides associated with the uncertain thing…”. In general, there may be many reasons for such situations within organisations. First, quite simplistically, in many cases where an adverse event has happened, this is typically due to multiple factors, and reasons can usually be found that diffuse responsibility. Second, an attitude can exist that it may be better not to spend time and resources discussing, identifying, and mitigating items that may not even happen, but rather to simply wait for them to (perhaps) happen and then deal with them: Indeed, such an approach will often be favoured as the practical and cost-effective one within an organisation; those promoting such approaches may also be regarded as the more powerful and action-oriented ones, who may also take a leading role in dealing with the consequences of any risks that do materialise.

It is also interesting to note that the use of risk assessment techniques may transfer some responsibility for poor outcomes away from modelling analysts and onto the decision-makers: Since there are many possible future outcomes to a situation, the realised outcome will almost always be different to the single outcome shown by a traditional static model. Thus, a single forecast that is provided to a decision-maker by a modelling analyst will always be wrong. Decision-makers may try to heuristically compensate for this to improve their decisions, based on the insufficient and ill-defined information provided. If high quality risk assessment models are used instead, then the realised outcome will be within the forecasted range: a poor outcome (if due to risk factors that were accounted for in the forecast) is essentially then the responsibility of the decision-maker or of project management, and so on. However, without the use of such models, some responsibility for bad outcomes can be placed on the modelling analyst, for having provided incomplete information in the first place.

Further, and rather subtly, the admission that some items are not controllable can create ambiguity within incentive systems, and this may also need to be managed carefully.

Exposing biases

As noted earlier, a robust risk and uncertainty assessment process (especially a quantitative one) will help to expose biases, whether they are structural, motivational/political or cognitive.

The simple example earlier demonstrating the “trap of the most likely” showed how even a simple uncertainty analysis can expose a structural bias. Other biases (especially political and motivational) can be exposed through a robust quantitative process in which an explicit distinction is made between the base case (fixed) assumption for the value of a variable and the uncertainty range associated with that variable. Of course, one of the barriers in exposing any form of bias is that doing so may not be politically acceptable. It may be difficult to admit that a project is likely to not be as profitable as first thought, or that it is likely to be delayed, or that there are risks or uncertainties that exist which cannot be controlled. There may be a political desire to delay the realisation of bad news, for example, or to hope that the situation may be improved before any bad news has been conveyed. Thus, the potential of risk and uncertainty assessment to expose biases can hinder its genuine implementation in some cases.

Beliefsaboutcomplexityofnewprocessesorefficacy of existing ones

The implementation of quantitative uncertainty assessment does require a change to existing analytic and decision-making processes (as well as to the cultural context around such activities).

In terms of the additional complexities that the introduction of risk or uncertainty assessment can pose, these can be thought of as analytic, process, change management and cultural challenges.

From an analytic perspective, the modelling of risk often requires more advanced skills to clearly design and structure models. Although the models can generally still be built in Excel (possibly with the use of Excel add- ins), the dynamic nature of risk models (i.e. to calculate many scenarios, each of which needs to be a genuinely valid outcome) often requires the use or development of modelling skills that may not originally be present within an organisation. On the other hand, it is worth noting that to some extent - since the aim of a model is, as far as practical, to represent reality (which is itself uncertain) - the modelling task is arguably more clearly defined than when it is based on input assumptions that are artificially fixed. Nevertheless, it is fair to say that the process of creating a model in which risks are mapped correctly is not always straightforward.

From a decision perspective, decision-makers also need to learn how to properly interpret the results of these new forms of analysis. This can add further complexity.

In terms of general processes, one may also need to add new forms of“gating processes” e.g. so that the depth of uncertainty analysis that is required to be undertaken is tailored to each project in a structured way. This may also require more cross-functional work, especially at the early stages of a project.

It is worth noting that some of the challenges may relate to the belief that existing analytic methods and decision- processes are already sufficient. For example, since such processes have been used to date, there may be perceived to be no compelling reason to change. Alternatively, risk and uncertainty assessment may be regarded as being already covered by a risk department, or by workshops that focus on operational risk factors. There can be scepticism as to the value for enhanced quantitative analysis. (On this point it is worth remarking that indeed, not least due to the “trap of the most likely”, traditional quantitative methods are structurally biased, so this scepticism has some basis in truth, with the solution being to expand the analytic framework to include risk and uncertainty). Finally, there may be a belief that risks should be dealt with by individual project managers and analysts doing their day-to-day jobs. All of these viewpoints can pose challenges, even as counterarguments can be made for each.

Common understanding and philosophy

The most challenging point to the widespread introduction of risk and uncertainty techniques relates to cultural issues. A “risk culture” is one in which there is a general, widespread and shared belief in the absolute requirement to formally assess risks and uncertainties, and a converse belief that a lack of such activity is not sufficient to create optimal and robust decisions, at least in aggregate.

As a rule, it is fair to say that there is a lack of “risk culture” within the general population, from which organisations typically draw their staff. This itself is a consequence of many underlying issues, including human instinct, different personality types, a lack of quantitative or statistical skills, and education systems that mostly focus on teaching us to develop and defend a specific position, rather than asking why we may be wrong. This lack of a common philosophy poses a significant challenge to the creation of a “risk culture” within an organisation.

6. Overcoming challenges

There is little doubt that the issues discussed above pose truly formidable challenges in the widespread and systematic implementation of risk and uncertainty assessment. As noted at the beginning of the article, the creation of the appropriate awareness, processes and culture are all core components in this respect. The most challenging of these is the cultural one; indeed, an organisation with a strong “risk culture” and common belief system would inherently be one in which there would be high awareness and in which the appropriate processes would have already been developed. At the same time, when it does not exist, the creation of such a culture would require one to first (or in parallel) generate a widespread level of awareness, and to develop process that participants are to follow.

Whilst the obstacles are significant, it is worth also highlighting some issues that can be borne in mind in trying to overcome these.

Is there an alternative?

The more challenging general environment for the oil and gas sector, the increasing need to have robust decision-making processes, and the enhanced requirements for corporate governance, mean that robust project evaluation and selection is more important than ever. In such contexts, the use of risk and uncertainty analysis is key to create insightful and accurate analysis. At its simplest level, it attempts only to capture the reality of a situation, so that accurate and relevant information about project and business economics can be provided to decision-makers. It would seem logical that the alternative (i.e. the continued use of traditional methods, and insufficient attention given to risks and uncertainties within project economics) will not be sufficient to generate future success, attract investment capital, develop profitable projects and negotiate the successful partnerships that will all be required for the sector to continue to attract investment.

Focussing on the benefits, maximising success and the benefit-cost ratio

In order to facilitate change, it is important to emphasise the benefits of new approaches (and the disadvantages of current ones). Many of these have been mentioned in this article. Further, it can be helpful to demonstrate the success of any new efforts made, and the benefits achieved from them. It is worth noting that some aspects of the success may in fact be of a qualitative (rather than quantitative) nature, in that the new processes can create a better understanding of a situation. Working groups should try to systemically note how their understanding and results have been influenced by the use of these new approaches, as a way of communicating the benefits more widely.

Top down change and leadership

Due to the challenges discussed earlier, particularly around cultural issues, “bottom-up approaches” alone are likely to fail. For example, a working group that is itself convinced of the benefits of such analysis, will likely fail when trying to use their results within the wider organisation, unless there is a shared understanding by all key players throughout the process. Thus, although small working groups of “champions” may be created for some technical or analytic issues, a wider change process needs to be introduced to enhance awareness and create a shared understanding and beliefs. This should not be overlooked, but rather be treated as a major change management exercise, which needs to be driven by top management. For example, one practical initiative that management can take is to themselves insist that these approaches are used for major projects, to introduce the processes and capability-development that is necessary, and to “walk the talk” (that is, to systematically see the results of risk assessments for all major projects, and to show that this approach is valued). This requires genuine leadership, not just management support. Further, other aspects of general change management approaches (communication, new systems and processes, capability enhancement etc.) need to be employed.

7. Final remarks

In this article, we have argued that the future success of the sector, and of individual companies within it, will more than ever depend on robust decision-making in the areas of project selection, project management, and business portfolio optimisation. More specifically, we have argued that this will require the widespread use of risk and uncertainty assessment approaches to generate a deep understanding of project economics, and to use this understanding to create more robust decision-making processes, as well as to improve outcomes in negotiations with private sector partners and governments. We have discussed the decision-making benefits in doing so, whilst recognising and analysing the key challenges in achieving the strong “risk cultures” that are necessary to successful and sustainable implementation. We have noted that the scale of the change management challenges means that strong and determined leadership is required. It is probably fair to say that the issues highlighted here are similar in Vietnam to in many other geographies around the world, even as the extent of implementation varies. It is important to enhance industry culture, capabilities and decision-making processes without undue delay.

References

1. Lord W.Douglas Cullen. The public inquiry into the Piper Alpha disaster. Great Britain. Department of Energy. 1990.

2. Jan-Erik Vinnem. Offshore risk assessment vol 1: Principles, modelling and applications of QRA studies. Springer. 2014.

3. Michael Rees. Businessriskandsimulationmodelling in practice: Using Excel, VBA and @RISK. John Wiley & Sons. 2015.

4. Jennifer L.Howell, Benjamin S.Crosier, James A.Shepperd. Does lacking threat-management resources increase information avoidance? A multi-sample, multi- method investigation. Journal of Research in Personality. 2014; 50: p. 102 - 109.

5. Deepwater Horizon Study Group. Final report on the investigation of the Macondo well blowout. 2011.